Peacekeeping

| Warfare |

|---|

|

Eras

Prehistoric

Ancient Medieval Gunpowder Industrial Modern Battlespace

Attrition warfare

Guerrilla warfare Maneuver warfare Siege Total war Trench warfare Conventional warfare Unconventional warfare Asymmetric warfare Counter-insurgency Network-centric warfare Cold war Proxy war Economic

Grand Operational Logistics

Technology and equipment

Materiel Supply chain management Lists

|

| Portal |

Peacekeeping is defined by the United Nations as "a unique and dynamic instrument developed by the Organization as a way to help countries torn by conflict create the conditions for lasting peace".[1] It is distinguished from both peacebuilding and peacemaking.

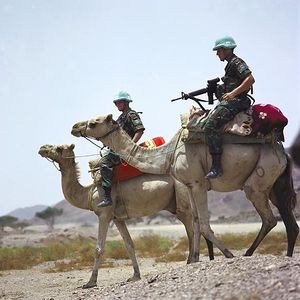

Peacekeepers monitor and observe peace processes in post-conflict areas and assist ex-combatants in implementing the peace agreements they may have signed. Such assistance comes in many forms, including confidence-building measures, power-sharing arrangements, electoral support, strengthening the rule of law, and economic and social development. Accordingly UN peacekeepers (often referred to as Blue Beret because of their light blue berets or helmets) can include soldiers, police officers, and civilian personnel.

The United Nations Charter gives the United Nations Security Council the power and responsibility to take collective action to maintain international peace and security. For this reason, the international community usually looks to the Security Council to authorize peacekeeping operations.

Most of these operations are established and implemented by the United Nations itself, with troops serving under UN operational control. In these cases, peacekeepers remain members of their respective armed forces, and do not constitute an independent "UN army", as the UN does not have such a force. In cases where direct UN involvement is not considered appropriate or feasible, the Council authorizes regional organizations such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Economic Community of West African States, or coalitions of willing countries to undertake peacekeeping or peace-enforcement tasks.

The United Nations is not the only organization to have authorized peacekeeping missions. Non-UN peacekeeping forces include the NATO mission in Kosovo and the Multinational Force and Observers on the Sinai Peninsula.

Alain Le Roy currently serves as the head of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO). DPKO's highest level doctrine document, entitled "United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Principles and Guidelines" was issued in 2008.[2]

Contents |

Nature of peacekeeping

Peacekeeping is anything that contributes to the furthering of a peace process, once established. This includes, but is not limited to, the monitoring of withdrawal by combatants from a former conflict area, the supervision of elections, and the provision of reconstruction aid. Peacekeepers are often soldiers, but they do not have to be. Similarly, while soldier-peacekeepers are sometimes armed, they do not have to engage in combat.

Peacekeepers were not at first expected to ever fight. As a general rule, they were deployed when the ceasefire was in place and the parties to the conflict had given their consent. They were deployed to observe from the ground and report impartially on adherence to the ceasefire, troop withdrawal or other elements of the peace agreement. This gave time and breathing space for diplomatic efforts to address the underlying causes of conflict.

Thus, a distinction must be drawn between peacekeeping and other operations aimed at peace. A common misconception is that activities such as NATO's intervention in the Kosovo War are peacekeeping operations, when they were, in reality, peace enforcement. That is, since NATO was seeking to impose peace, rather than maintain peace, they were not peacekeepers, rather peacemakers.

Process and structure

Formation

Once a peace treaty has been negotiated, the parties involved might ask the United Nations for a peacekeeping force to oversee various elements of the agreed upon plan. This is often done because a group controlled by the United Nations is less likely to follow the interests of any one party, since it itself is controlled by many groups, namely the 15-member Security Council and the intentionally-diverse United Nations Secretariat.

If the Security Council approves the creation of a mission, then the Department of Peacekeeping Operations begins planning for the necessary elements. At this point, the senior leadership team is selected (see below). The department will then seek contributions from member nations. Since the UN has no standing force or supplies, it must form ad hoc coalitions for every task undertaken. Doing so results in both the possibility of failure to form a suitable force, and a general slowdown in procurement once the operation is in the field. Romeo Dallaire, force commander in Rwanda during the Rwandan Genocide there, described the problems this poses by comparison to more traditional military deployments:

"He told me the UN was a 'pull' system, not a 'push' system like I had been used to with NATO, because the UN had absolutely no pool of resources to draw on. You had to make a request for everything you needed, and then you had to wait while that request was analyzed...For instance, soldiers everywhere have to eat and drink. In a push system, food and water for the number of soldiers deployed is automatically supplied. In a pull system, you have to ask for those rations, and no common sense seems to ever apply." (Shake Hands With the Devil, Dallaire, pp. 99-100)

While the peacekeeping force is being assembled, a variety of diplomatic activities are being undertaken by UN staff. The exact size and strength of the force must be agreed to by the government of the nation whose territory the conflict is on. The Rules of Engagement must be developed and approved by both the parties involved and the Security Council. These give the specific mandate and scope of the mission (e.g. when may the peacekeepers, if armed, use force, and where may they go within the host nation). Often, it will be mandated that peacekeepers have host government minders with them whenever they leave their base. This complexity has caused problems in the field.

When all agreements are in place, the required personnel are assembled, and final approval has been given by the Security Council, the peacekeepers are deployed to the region in question.

Cost

Peacekeeping costs, especially since the end of the Cold War, have risen dramatically. In 1993, annual UN peacekeeping costs had peaked at some $3.6 billion, reflecting the expense of operations in the former Yugoslavia and Somalia. By 1998, costs had dropped to just under $1 billion. With the resurgence of larger-scale operations, costs for UN peacekeeping rose to $3 billion in 2001. In 2004, the approved budget was $2.8 billion, although the total amount was higher than that. For the fiscal year which ended on June 30, 2006, UN peacekeeping costs were about US$5.03 billion.

All member states are legally obliged to pay their share of peacekeeping costs under a complex formula that they themselves have established. Despite this legal obligation, member states owed approximately $1.20 billion in current and back peacekeeping dues as of June 2004.

Structure

A United Nations peacekeeping mission has three power centers. The first is the Special Representative of the Secretary-General, the official leader of the mission. This person is responsible for all political and diplomatic activity, overseeing relations with both the parties to the peace treaty and the UN member-states in general. They are often a senior member of the Secretariat. The second is the Force Commander, who is responsible for the military forces deployed. They are a senior officer of their nation's armed services, and are often from the nation committing the highest number of troops to the project. Finally, the Chief Administrative Officer oversees supplies and logistics, and coordinates the procurement of any supplies needed.

History

Cold War Peacekeeping

United Nations peacekeeping was initially developed during the Cold War as a means of resolving conflicts between states by deploying unarmed or lightly armed military personnel from a number of countries, under UN command, to areas where warring parties were in need of a neutral party to observe the peace process. Peacekeepers could be called in when the major international powers (the five permanent members of the Security Council) tasked the UN with bringing closure to conflicts threatening regional stability and international peace and security. These included a number of so-called "proxy wars" waged by client states of the superpowers. As of February 2009, there have been 63 UN peacekeeping operations since 1948, with sixteen operations ongoing. Suggestions for new missions arise every year.

The first peacekeeping mission was launched in 1948. This mission, the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO), was sent to the newly created State of Israel, where a conflict between the Israelis and the Arab states over the creation of Israel had just reached a ceasefire. The UNTSO remains in operation to this day, although the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict has certainly not abated. Almost a year later, the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) was authorized to monitor relations between the two nations, which were split off from each other following the United Kingdom's decolonization of the Indian subcontinent.

As The Korean War entered a cease-fire in 1953, UN forces remained along the south side of demilitarized zone until 1967, when American and South Korean forces took over.

Returning its attention to the conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors, the United Nations responded to Suez Crisis of 1956, a war between the alliance of the United Kingdom, France, and Israel, and Egypt, which was supported by other Arab nations. When a ceasefire was declared in 1957, Canadian diplomat (and future Prime Minister) Lester Bowles Pearson suggested that the United Nations station a peacekeeping force in the Suez in order to ensure that the ceasefire was honored by both sides. Pearson had initially suggested that the force consist of mainly Canadian soldiers, but the Egyptians were suspicious of having a Commonwealth nation defend them against the United Kingdom and her allies. In the end, a wide variety of national forces were drawn upon to ensure national diversity. Pearson would win the Nobel Peace Prize for this work, and he is today considered a father of modern peacekeeping.

In 1988 the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the United Nations peacekeeping forces. The press release stated that the forces "represent the manifest will of the community of nations" and have "made a decisive contribution" to the resolution of conflict around the world.

Since 1991

The end of the Cold War precipitated a dramatic shift in UN and multilateral peacekeeping. In a new spirit of cooperation, the Security Council established larger and more complex UN peacekeeping missions, often to help implement comprehensive peace agreements between protagonists in intra-State conflicts and civil wars. Furthermore, peacekeeping came to involve more and more non-military elements that ensured the proper functioning of civic functions, such as elections. The UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations was created in 1992 to support this increased demand for such missions.

By and large, the new operations were successful. In El Salvador and Mozambique, for example, peacekeeping provided ways to achieve self-sustaining peace. Some efforts failed, perhaps as the result of an overly optimistic assessment of what UN peacekeeping could accomplish. While complex missions in Cambodia and Mozambique were ongoing, the Security Council dispatched peacekeepers to conflict zones like Somalia, where neither ceasefires nor the consent of all the parties in conflict had been secured. These operations did not have the manpower, nor were they supported by the required political will, to implement their mandates. The failures — most notably the 1994 Rwandan genocide and the 1995 massacre in Srebrenica and Bosnia and Herzegovina — led to a period of retrenchment and self-examination in UN peacekeeping.

Gallantry Awards

- Captain Salaria - Congo

In November 1961 the UN Security Council moved to prevent hostilities by Katangese troops in Congo. This caused Moise Tshombe, the Katanga secessionist leader to step up attacks on UN troops. On 5 December 1961, an Indian UN company supported by 3-inch mortar attacked a Katangese road-block between the Katangese HQ and the Elisabethville airfield. A Gurkha platoon attempted to link up with the company and reinforce the road-block, but ran into opposition near the old airfield. The platoon attack on the rebel position, manned by about 90 Katangese troops, was lead by Indian Captain Gurbachan Singh Salaria. Despite having only 16 soldiers and being outgunned, Captain Salaria and his Gurkha soldiers' ferocity overwhelmed the enemy, who fled. In this engagement, Captain Salaria was shot in his neck, but continued to fight till he succumbed to his injuries. Due to his selfless act of courage, the UN Headquarters in Elisabethville was saved from encirclement and Captain Salaria was awarded India's highest military award, the Param Vir Chakra.[3][4]

Non-United Nations Peacekeeping

Not all peacekeeping forces have been directly controlled by the United Nations. In 1981, an agreement between Israel and Egypt formed the Multinational Force and Observers which continues to monitor the Sinai Peninsula.

Six years later, the Indian Peace Keeping Force entered Sri Lanka to help maintain peace. The situation became a quagmire, and India was asked to withdraw in 1990 by the Sri Lankan Prime Minister having formed a pact with the Tamil Tiger rebels.

In November 1988, India also helped restore government of Maumoon Abdul Gayoom in Maldives under Operation Cactus.

On 20 December 1995, under a UN mandate, a NATO-led force (IFOR) entered Bosnia in order to implement The General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In a similar manner, a NATO operation (KFOR) continues in the former Serbian province of Kosovo.

The NATO-led mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina has since been replaced by a European Union peacekeeping mission, EUFOR.

The African Union has also had some limited involvement in peacekeeping within Africa since 2003.

In South Ossetia, Russia and Georgia each deployed their own sets of peacekeepers to the region under the Sochi agreement. The 2008 South Ossetia War resulted in the expulsion of all Georgian forces from the region, including peacekeepers, as well as the deaths of 18 Russian peacekeepers.

Participation

The UN Charter stipulates that to assist in maintaining peace and security around the world, all member states of the UN should make available to the Security Council necessary armed forces and facilities. Since 1948, close to 130 nations have contributed military and civilian police personnel to peace operations. While detailed records of all personnel who have served in peacekeeping missions since 1948 are not available, it is estimated that up to one million soldiers, police officers and civilians have served under the UN flag in the last 56 years. As of March 2008, 113 countries were contributing a total 88,862 military observers, police, and troops.[5]

Despite the large number of contributors, the greatest burden continues to be borne by a core group of developing countries, who often profit financially from their participation in such missions. The 10 main troop-contributing countries to UN peacekeeping operations as of March 2007 were Pakistan (10,173), Bangladesh (9,675), India (9,471), Nepal (3,626), Jordan (3,564), Uruguay (2,583), Italy (2,539), Ghana (2,907), Nigeria (2,465), and France (1,975).[6]

The head of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Under-Secretary-General Jean-Marie Guéhenno, has reminded Member States that “the provision of well-equipped, well-trained and disciplined military and police personnel to UN peacekeeping operations is a collective responsibility of Member States. Countries from the South should not and must not be expected to shoulder this burden alone”.

As of March 2008, in addition to military and police personnel, 5,187 international civilian personnel, 2,031 UN Volunteers and 12,036 local civilian personnel worked in UN peacekeeping missions.[7]

Through April 2008, 2,468 people from over 100 countries have been killed while serving on peacekeeping missions.[8] Many of those came from India (127), Canada (114) and Ghana (113). Thirty percent of the fatalities in the first 55 years of UN peacekeeping occurred in the years 1993-1995.

Developing nations tend to participate in peacekeeping more than developed countries. This may be due in part because forces from smaller countries avoid evoking thoughts of imperialism. For example, in December 2005, Eritrea expelled all American, Russian, European, and Canadian personnel from the peacekeeping mission on their border with Ethiopia. Additionally, an economic motive appeals to the developing countries. The rate of reimbursement by the UN for troop contributing countries per peacekeeper per month include: $1,028 for pay and allowances; $303 supplementary pay for specialists; $68 for personal clothing, gear and equipment; and $5 for personal weaponry.[9] This can be a significant source of revenue for a developing country. By providing important training and equipment for the soldiers as well as salaries, UN peacekeeping missions allow them to maintain larger armies than they otherwise could. About 4.5% of the troops and civilian police deployed in UN peacekeeping missions come from the European Union and less than one percent from the United States (USA).[10] Both personnel and financial contributions to peacekeeping opeations are included in the Commitment to Development Index, which ranks donor governments on their policies to the developing world.

Criticism

Potential for harm to troops

There is some concern about the harm caused to troops, as peacekeeping can be very stressful. The peacekeepers are exposed to danger caused by the warring parties and often in an unfamiliar climate. This gives rise to different mental health problems, suicide, and substance abuse as shown by the percentage of former peacekeepers with those problems. Having a parent in a mission abroad for an extended period is also stressful to the peacekeepers' family.[11] In addition, peacekeepers, even when acting on UN mandate, may become a target for attacks by some of the parties in a conflict.

Another viewpoint raises the problem that the peacekeeping may soften the troops and erode their combat ability, as the mission profile of a peacekeeping contingent is totally different from the profile of a unit fighting an all-out war.[12][13]

Peacekeeping, human trafficking, and forced prostitution

Reporters witnessed a rapid increase in prostitution in Cambodia, Mozambique, Bosnia, and Kosovo after UN and, in the case of the latter two, NATO peacekeeping forces moved in. In the 1996 U.N. study The Impact of Armed Conflict on Children, former first lady of Mozambique Graça Machel documented: "In 6 out of 12 country studies on sexual exploitation of children in situations of armed conflict prepared for the present report, the arrival of peacekeeping troops has been associated with a rapid rise in child prostitution."[14]

Gita Sahgal spoke out in 2004 with regard to the fact that prostitution and sex abuse crops up wherever humanitarian intervention efforts are set up. She observed: "The issue with the UN is that peacekeeping operations unfortunately seem to be doing the same thing that other militaries do. Even the guardians have to be guarded."[15]

Criticisms of scandals

Oil-for-Food Programme scandal

In addition to criticism of the basic approach, the Oil-for-Food Programme suffered from widespread corruption and abuse. Throughout its existence, the programme was dogged by accusations that some of its profits were unlawfully diverted to the government of Iraq and to UN officials.[16]

Peacekeeping child sexual abuse scandal

Reporters witnessed a rapid increase in prostitution in Cambodia, Mozambique, Bosnia, and Kosovo after UN and, in the case of the latter two, NATO peacekeeping forces moved in. In the 1996 U.N. study The Impact of Armed Conflict on Children, former first lady of Mozambique Graça Machel documented: "In 6 out of 12 country studies on sexual exploitation of children in situations of armed conflict prepared for the present report, the arrival of peacekeeping troops has been associated with a rapid rise in child prostitution."[14]

Human Rights in United Nations missions

The following table chart illustrates confirmed accounts of crimes and human rights violations committed by United Nations soldiers, peacekeepers and employees.[17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28]

| Conflict | United Nations Mission | Sexual abuse1 | Murder2 | Extortion/Theft3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Congo War | United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo | 150 | 3 | 44 |

| Somali Civil War | United Nations Operation in Somalia II | 5 | 24 | 5 |

| Sierra Leone Civil War | United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone | 50 | 7 | 15 |

| Eritrean-Ethiopian War | United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea | 70 | 15 | unknown |

| Burundi Civil War | United Nations Operation in Burundi | 80 | 5 | unknown |

| Rwanda Civil War | United Nations Observer Mission Uganda-Rwanda | 65 | 15 | unknown |

| Liberian Civil War | United Nations Mission in Liberia | 30 | 4 | 1 |

| Second Sudanese Civil War | United Nations Mission in Sudan | 400 | 5 | unknown |

| Côte d'Ivoire Civil War | United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire | 500 | 2 | unknown |

| 2004 Haiti rebellion | United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti | 110 | 57 | unknown |

| Kosovo War | United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo | 800 | 70 | 100 |

| Israeli–Lebanese conflict | United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon | unknown | 6 | unknown |

Proposed reform

Brahimi analysis

In response to criticism, particularly of the cases of sexual abuse by peacekeepers, the UN has taken steps toward reforming its operations. The Brahimi Report was the first of many steps to recap former peacekeeping missions, isolate flaws, and take steps to patch these mistakes to ensure the efficiency of future peacekeeping missions. The UN has vowed to continue to put these practices into effect when performing peacekeeping operations in the future. The technocratic aspects of the reform process have been continued and revitalised by the DPKO in its 'Peace Operations 2010' reform agenda. The 2008 capstone doctrine entitled "United Nations Peacekeeping Operations: Principles and Guidelines"[2] incorporates and builds on the Brahimi analysis.

Rapid reaction force

One suggestion to account for delays such as the one in Rwanda, is a rapid reaction force: a standing group, administered by the UN and deployed by the Security Council, that receives its troops and support from current Security Council members and is ready for quick deployment in the event of future genocides.

See also

- UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations

- List of all UN peacekeeping missions

- List of countries where UN peacekeepers are currently deployed

- List of non-UN peacekeeping missions

- Multinational Force and Observers

- Timeline of UN peacekeeping missions

- Military operations other than war

- Three Block War

- White Helmets

- PKSOI

References

- ↑ United Nations Peacekeeping

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 DPKO Capstone Doctrine

- ↑ Rakshak, Bharat (undated). "Captain Gurbachan Singh Salaria". http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/HEROISM/Salaria.html. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ↑ Shorey, Anil (April 2004). "CAPTAIN COURAGE". http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/ARMY/History/1950s/Courage.html. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ↑ Contributors to United Nations peacekeeping operations

- ↑ "Monthly Summary of Contributors to UN Peacekeeping Operations" (PDF). http://www.un.org/Depts/dpko/dpko/contributors/2007/march07_2.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ↑ Background Note - United Nations Peacekeeping Operations

- ↑ United Nations peacekeeping - Fatalities By Year up to 31 Dec 2008

- ↑ United Nations Peacekeepers - How are peacekeepers compensated?

- ↑ UN Peacekeeping FactSheet

- ↑ Lanan torjuntaa – Henkinen hyvinvointi rauhanturvajoukoissa. Kipunoita 2/2003. Retrieved 9-3-2007. (Finnish)

- ↑ Kaurin, P. M. (2007) War Stories: Narrative, Identity and (Recasting) Military Ethics Pedagogy. Pacific Lutheran University. ISME 2007. Retrieved 9-3-2007

- ↑ Liu, H. C. K., The war that could destroy both armies, Asia Times, 23 October 2003. Retrieved 9-3-2007.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 The Impact of Armed Conflict on Children

- ↑ Sex charges haunt UN forces; In places like Congo and Kosovo, peacekeepers have been accused of abusing the people they're protecting," Christian Science Monitor, 26 November 2004, accessed 16 February 2010

- ↑ Oil-for-food chief 'took bribes'

- ↑ 1 : compiled from the corresponding Wikipedia articles. When a range was given, the median was used.

- ↑ 2 http://www.unwire.org/unwire/20030411/33133_story.asp United Nations Foundation.

- ↑ 3http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A52333-2005Mar20.html Congo's Desperate 'One-Dollar U.N. Girls'

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/6195830.stm UN troops face child abuse claims

- ↑ http://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/005/081zxelz.asp The U.N. Sex Scandal

- ↑ http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/un-troops-buy-sex-from-teenage-refugees-in-congo-camp-756666.html UN troops buy sex from teenage refugees in Congo camp

- ↑ http://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/199/40816.html UN Peacekeepers Criticized

- ↑ http://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/190/32956.html Global Rules Now Apply to Peacekeepers

- ↑ http://law.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3113&context=expresso Victims of Peace: Current Abuse Allegations against U.N. Peacekeepers and the Role of Law in Preventing Them in the Future

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/27_05_08_savethechildren.pdf No One to Turn To - BBC Analysis

- ↑ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1538476/UN-staff-accused-of-raping-children-in-Sudan.html UN staff accused of raping children in Sudan

- ↑ http://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/2002/bosnia/ TRAFFICKING OF WOMEN AND GIRLS TO POST-CONFLICT BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FOR FORCED PROSTITUTION - Human Rights Watch

Further reading

- Bureš, Oldřich (June 2006). "Regional Peacekeeping Operations: Complementing or Undermining the United Nations Security Council?". Global Change, Peace & Security 18 (2): 83–99. doi:10.1080/14781150600687775.

- Fortna, Virginia Page (2004). "Does Peacekeeping Keep Peace? International Intervention and the Duration of Peace After Civil War". International Studies Quarterly 48: 269–292. doi:10.1111/j.0020-8833.2004.00301.x.

- Goulding, Marrack (July 1993). "The Evolution of United Nations Peacekeeping". International Affairs (International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), Vol. 69, No. 3) 69 (3): 451–64. doi:10.2307/2622309. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0020-5850(199307)69%3A3%3C451%3ATEOUNP%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X.

- Pushkina, Darya (June 2006). "A Recipe for Success? Ingredients of a Successful Peacekeeping Mission". International Peacekeeping 13 (2): 133–149. doi:10.1080/13533310500436508.

- Worboys. Katherine. 2007. “The Traumatic Journey from Dictatorship to Democracy: Peacekeeping Operations and Civil-Military Relations in Argentina, 1989-1999.” Armed Forces & Society, vol. 33: pp. 149–168. abstract

- Dandeker, Christopher and James Gow. 1997. “The Future of Peace Support Operations: Strategic Peacekeeping and Success.” Armed Forces & Society, vol. 23: pp. 327–347. abstract

- Blocq, Daniel. 2009. “Western Soldiers and the Protection of Local Civilians in UN Peacekeeping Operations: Is a Nationalist Orientation in the Armed Forces Hindering Our Preparedness to Fight?” Armed Forces & Society, abstract

- Bridges, Donna and Debbie Horsfall. 2009. “Increasing Operational Effectiveness in UN Peacekeeping: Toward a Gender-Balanced Force.” Armed Forces & Society, May 2009. abstract

- Reed, Brian and David Segal. 2000. “The Impact of Multiple Deployments on Soldiers’ Peacekeeping Attitudes, Morale and Retention.” Armed Forces & Society, vol. 27: pp. 57-78. abstract

- Sion, Liora. 2006. “’Too Sweet and Innocent for War’?: Dutch Peacekeepers and the Use of Violence.” Armed Forces & Society, vol. 32: pp. 454–474. abstract

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||